Highest & Best Use: 6 Strategies for Responsible Land Use

Back in the early 1900s, economic theory revolved around utility—how resources could be allocated most efficiently and purposefully. Land, being a tangible and finite resource, was central to these discussions. However, as society evolved from agrarian roots into more diverse land uses, the utility of smaller parcels became harder to quantify.

Developers and real estate speculators introduced the concept of “highest and best use” to solve this problem. It provided a framework for evaluating the most valuable and practical application of land, considering what is physically possible, legally permissible, financially feasible, commercially profitable, and aligned with community interests. For example, a plot in a dense city is more valuable as a multi-story apartment building than a parking lot, as it meets greater demand and generates more income.

Though the core principles of highest and best use remain, modern developers now rely on sophisticated data tools to fine-tune their assessments. By evaluating zoning regulations, market trends, and construction costs, developers aim to optimize land for both profit and functionality.

At HUTS, where our focus is on rural residential development, we take a slightly different approach. We’re as concerned with preserving natural environments as we are with profitability (and we’ve seen the pursuit of both simultaneously as a sound development model). We aim to minimize our ecological footprint and think long-term about the experience each property can offer—to the people, wildlife, and landscapes it supports—after construction is complete.

Over the past four years, we’ve analyzed more than 3,000 land parcels through our work on land.nyc, The Land Report, and client-specific sourcing efforts. Each parcel offers unique challenges and opportunities.

Below are six strategies we’ve identified to deliver what we call the Highest and Best Experience on rural lots:

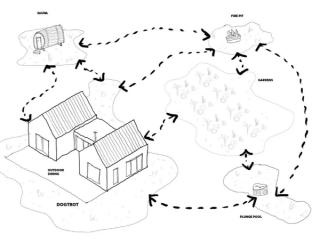

1. Recreational Amenity Circuit

This strategy encourages residents to explore every corner of their property. Imagine a 10-acre lot with a creek at the back, a meadow near the road, and a forested area. Rather than clear trees and extend utilities all the way to the creek, the home is built in the meadow. From there, a walking trail connects curated outdoor experiences—a writer’s cabin on piers in the forest, a wood-fired sauna by the creek, and an outdoor dining space with solar lights in the trees. The result is an atomized living experience, where the home’s amenities are dispersed across the landscape and connected by a lightly defined path.

See an example of a recreational amenity circuit

2. ADU First, Main House Second

Instead of building a primary residence first, we recommend starting with the ADU (Accessory Dwelling Unit). This smaller structure provides an immediate place to stay, helping residents get acquainted with the land. An ADU is often more affordable, can be financed directly, and boosts property value—improving the owner’s position for future construction financing. Once the ADU is in place, the main house can follow.

See and example of ADU First, Main House Second

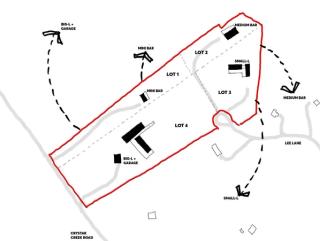

3. Pocket Community

In rural districts where zoning limits large-scale development, we see opportunities for pocket communities. For example, a 20-acre parcel in a 5-acre minimum zoning area could be subdivided into four lots (each with 4.5 acres), with a shared driveway and two acres reserved as a community amenity, such as an orchard. This strategy ensures privacy and preservation of the rural character while fostering a sense of community through shared spaces.

See an example of a Pocket Community

4. Keep-One Subdivision

Many landowners seek enough acreage for privacy, but not so much that it becomes a burden to maintain. For clients in these situations, we often advise purchasing slightly more land than needed and subdividing it into two lots. The owner builds on one lot, while the other turnkey build site is sold to subsidize construction costs.

See and example of a Keep-One Subdivision

5. Multi-Generational Living / Family Compound

This strategy addresses the growing trend of multi-generational living. Instead of building a single large home, we design several smaller structures connected by outdoor walkways and breezeways—providing both shared and private spaces. From a zoning perspective, the property remains a single-family home serviced by a single set of infrastructure, avoiding the need for complex entitlements. However, the layout creates the feel of a family compound, balancing independence with connection.

See an example of a Family Compound

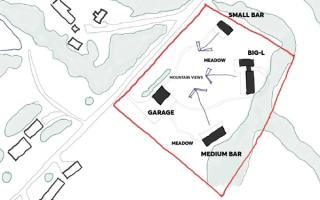

6. Live / Work Arrangement

Many HUTS clients are makers, artisans, and tinkerers who need workshop spaces. For them, we design live/work environments that align with zoning regulations and lifestyle needs. A typical layout might place the home in a meadow, with the workshop nestled within nearby trees to create a natural sense of separation. A trail connecting the two spaces offers a symbolic “commute,” helping residents mentally shift between work and home life. Thoughtful land design reinforces the rhythms of a productive day, with natural elements offering moments of rest and inspiration.

See an example of a Live/Work Arrangement

At HUTS, we believe that land development should balance experience and economics, and that the two are not mutually-exclusive. The strategies we’ve identified go beyond maximizing property value—they aim to enhance the lived experience over time. Whether it’s creating a walking path through the landscape, building an ADU before the main house, or fostering a pocket community, our goal is to deliver developments that feel rooted, intentional, and enduring. By prioritizing the long-term experience of place, we’re helping landowners cultivate not just homes, but meaningful connections to their property..

Disclaimer The land use strategies outlined in this article are intended for individual landowners and small-scale family compounds. While HUTS also engages in larger-scale projects, including hospitality developments and municipal initiatives, the concepts presented here are tailored specifically to single-family residences and smaller, private properties. For larger or more complex projects, such as resorts, community planning, or public infrastructure, we apply different frameworks and approaches suited to the unique challenges and opportunities of those developments.